Poetry magazine asked Jan. 2016 issue contributors to tell them what we have been reading. I wrote this for them. Read this post on Poetry Magazine's website here

I’ve been reading the World Wildlife Fund’s April 2015 scientific report, “State of the Amazon: Freshwater Connectivity and Ecosystem Health.” First of all, it’s amazing to learn that, in rivers with flood pulses that raise water levels, Amazonian fish don’t stay in the river channel. When rainfall and seasonal pulses flood adjacent riparian areas, fish roam into these areas, avoiding predators, seeking resources unavailable in the river, including plant detritus and seeds in nutrient-rich water. They also find nesting and egg-laying areas. Scientists call this “lateral connectivity.” In addition to fish that boost survival rates as they migrate to floodplain resources, other creatures depend on floodplains: pink-nosed and other dolphins, giant turtles, caimans, and otters. Terrestrial animals use riparian areas as migration corridors, including jaguars, tapirs, and peccaries.

However, due to an unprecedented rise in development in the Amazon in the last 5-10 years—primarily dam construction, and also mining, cattle ranching, and agriculture—these freshwater ecosystems are being altered, and with them, the aquatic animals’ abilities to travel between rivers and surrounding riparian areas. In the Upper Xingu River Basin (Brazil) alone, there are 10,000 small dams, 1 every 4 miles. The created water reservoirs change water quality—temperature and sediment level upstream and downstream, and alter water discharge levels (which correlates with decreased rainfall). Where river sediment grains are larger, as the giant Amazon river turtle and yellow-spotted side-neck turtle nest, their eggs’ survival rates have decreased.

In Brazil’s share of the Amazon Basin alone, there are 138 operational, 16 under-construction, and 221 planned large dams—each of which involves removing from their river land tens of thousands of indigenous and traditional river peoples.

In June 2016, when I go to the Tapajos River basin, I will observe this up close. I will post updates here!

As for poetry, I recently finished reading Multitudinous Heart: Selected Poems by Carlos Drummond de Andrade, translated by Richard Zenith.

Read my post on Poetry Magazine's website here

Showing posts with label Brazil. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Brazil. Show all posts

Saturday, February 20, 2016

Monday, November 16, 2015

Wildfires in the Chapada Diamantina

Sad to see that Chapada National Park and surrounding towns in the Chapada Diamantina in Bahia, Brazil, are burning.

According to César Gonçalves, the acting director of Chapada National Park, the situation is “out of control.”

In this video in Portuguese (beware the 30 sec. ad), the park director on Nov. 16 reiterates that the fire is out of control, but then comes the Secretary of the Environment Eugenio Spengler who insists that, no, really, it’s under control. Except that the aerial views in this video look anything but.

I backpacked there in January 2013, and it was a gorgeous respite from the city. I immediately felt at home there, as if a sudden calm had overtaken me, quieting any anxieties. That first night, I slept a deep sleep, and awakened late to bird song, a kind of symphony the likes of which I'd never heard. I ceased all motion, laying only in the hammock in the yellow-green sea of grasses, listening for hours. After I finally budged to breakfast with a sleepwalker's motions, I went out to walk. Yellow butterflies glutted the air of the valley of Capão, as if it were enchanted. I know that I was –- enchanted, that is.

Gonçalves said that they have three separate fires, “one in Ibicioara, where Ibama [the federal environmental agency] is combating areas that lay outside the park; a big fire in the north region of the park, between the municipalities of Lençóis e Palmeiras; and one in Morro Branco, in the Valley of Capão.”

As of Nov. 14, the fourth day of the fires, there didn’t seem to be any improvement in containment. An initial fire began on Nov. 12, near to the Mucugezinho River, which separates the towns of Lençóis and Palmeiras. Dry air, lack of rain, and strong winds have spread the fires.

Residents of the region complain that the quantity of professionals and volunteers combating the fire is insufficient. Residents of Bahia who feel that the government is allocating insufficient resources to fight the fires are organizing around the hashtag #soschapadadiamantina

On Nov. 14, police detained a man suspected of lighting the fire in the park. Gildásio Miranda Silva, native of the nearby town of Mucugê, was arrested after being caught in the act of lighting the fire, according to the Jornal da Chapada.

According to César Gonçalves, the acting director of Chapada National Park, the situation is “out of control.”

In this video in Portuguese (beware the 30 sec. ad), the park director on Nov. 16 reiterates that the fire is out of control, but then comes the Secretary of the Environment Eugenio Spengler who insists that, no, really, it’s under control. Except that the aerial views in this video look anything but.

I backpacked there in January 2013, and it was a gorgeous respite from the city. I immediately felt at home there, as if a sudden calm had overtaken me, quieting any anxieties. That first night, I slept a deep sleep, and awakened late to bird song, a kind of symphony the likes of which I'd never heard. I ceased all motion, laying only in the hammock in the yellow-green sea of grasses, listening for hours. After I finally budged to breakfast with a sleepwalker's motions, I went out to walk. Yellow butterflies glutted the air of the valley of Capão, as if it were enchanted. I know that I was –- enchanted, that is.

Gonçalves said that they have three separate fires, “one in Ibicioara, where Ibama [the federal environmental agency] is combating areas that lay outside the park; a big fire in the north region of the park, between the municipalities of Lençóis e Palmeiras; and one in Morro Branco, in the Valley of Capão.”

As of Nov. 14, the fourth day of the fires, there didn’t seem to be any improvement in containment. An initial fire began on Nov. 12, near to the Mucugezinho River, which separates the towns of Lençóis and Palmeiras. Dry air, lack of rain, and strong winds have spread the fires.

Residents of the region complain that the quantity of professionals and volunteers combating the fire is insufficient. Residents of Bahia who feel that the government is allocating insufficient resources to fight the fires are organizing around the hashtag #soschapadadiamantina

On Nov. 14, police detained a man suspected of lighting the fire in the park. Gildásio Miranda Silva, native of the nearby town of Mucugê, was arrested after being caught in the act of lighting the fire, according to the Jornal da Chapada.

Sunday, November 8, 2015

Vale SA Mining Company Dam Fails, Brazil's Biggest Dam Break

On Nov. 5 in the district of Bento Rodrigues in the town of Marianas in Minas Gerais state, Brazil, the Samarco mining operation's tailings dam failed, pouring 60 million cubic tons of water and iron ore waste into the town. This amounted to a gargantuan wave of mud, which is still flowing at this writing, continuing to devastate the surrounding area. Authorities are unable to enter the area, with only drones providing area pictures of the wide, spreading swath of green land affected. Two people are confirmed killed, and 28 people are still missing. It looks to be Brazil's biggest dam break ever.

Samarco is a joint venture of BHP Billiton Ltd. and Vale SA, two of the world’s biggest mining companies.

The dam's alarm system did not sound, leaving the residents without warning besides impromptu help provided by good Samaritans who helped some to evacuate. They only knew a dam had broken when some noticed a big cloud of dust in the sky 4 miles away in the direction of the dam. One man jumped on a flatbed and drove around yelling for people to flee; he was able to get out 60 people, including some elders. Meanwhile, others missed this improvised rescue operation. 200 homes were destroyed, with 800 left homeless.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the residents of Bento Rodrigues reported that they had lived in fear of the dam put above their town, in their observation, without structural reinforcement. It appeared to be propped up with mounds of clay, and residents said that they were made nervous by seeing dam workers constantly patching parts of the dam. The residents had asked the company to improve safety--which met with no Vale actions to address residents' concerns.

According to Places of Minas's online commentary (Lugares de Minas), this break is not singular but points to a bigger pattern of greed and land exploitation in the region. They ask, "Até quando Brasil? Cadê os órgãos responsáveis, que deveriam fiscalizar? Quantas comunidades, cidades, não estão no mesmo risco?" or, "How long will this go on, Brazil? Where are the responsible government bodies which should be regulating this activity? How many communities and cities are in the same danger?"

I actually have some personal experience with Vale mining company. In 2010, when I visited Minas Gerais, driving between Belo Horizonte and Ouro Preto, the beautiful green rolling hills were often gashed with orange, dramatically cut away. Curious, and suspicious of the roadside billboards describing how eco-friendly Vale was (which we suspected was so much green washing), we pulled off to the side of the road. We followed our noses off the ramp and up to a guard station that served as checkpoint into the Vale mined area. The station house was stocked with fully militarized guards, in paramilitary gear. We innocently asked if we could tour the facilities. This met with no smile cracked in the faces whose eyes were hidden behind shaded glasses. We hurriedly made a U-turn and left the way we had come, our curiosity about Vale's operations unquenched, but with a strong instruction in Vale's security system. Security, that is, for the operations--less so for nearby residents.

A tailings dam is built to shore up mine waste and water produced in the milling process. Sometimes in tailing ponds, other minerals are mixed with the mining waste in order to slow its dispersal into the environment. According to Scott Dunbar, department head of the Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering at the University of British Columbia, tailings dams usually fail from excess of water in the tailings ponds. The people in the town were not warned.

The destruction of the town of Bento Rodrigues is all the more sad given the town's women's cooperative that collaborated to grow and harvest local fruits and chili peppers in order to make local delicacies that they sold in jars. This artisanal collective of poor rural women who harvested the land traditionally to create their own business--is now destroyed, primarily because the land, and all their homes and cooking facilities, were destroyed in the giant wave of mud. Watch this video to see how the land looked prior to the Samargo mining company's dam fail. It is so peaceful and bucolic, it is truly heart breaking to think of these women entrepreneurs' efforts, and traditional lives, literally soiled and in ruins.

The destruction of the town of Bento Rodrigues is all the more sad given the town's women's cooperative that collaborated to grow and harvest local fruits and chili peppers in order to make local delicacies that they sold in jars. This artisanal collective of poor rural women who harvested the land traditionally to create their own business--is now destroyed, primarily because the land, and all their homes and cooking facilities, were destroyed in the giant wave of mud. Watch this video to see how the land looked prior to the Samargo mining company's dam fail. It is so peaceful and bucolic, it is truly heart breaking to think of these women entrepreneurs' efforts, and traditional lives, literally soiled and in ruins.This is personally upsetting for me, knowing how people in country areas of Minas Gerais struggle to maintain a traditional lifestyle of tending the land--in the face of expanding mining operations.

Saturday, September 19, 2015

Guarani-Kaiowá Leader Killed in Retaliation for Land Reoccupation

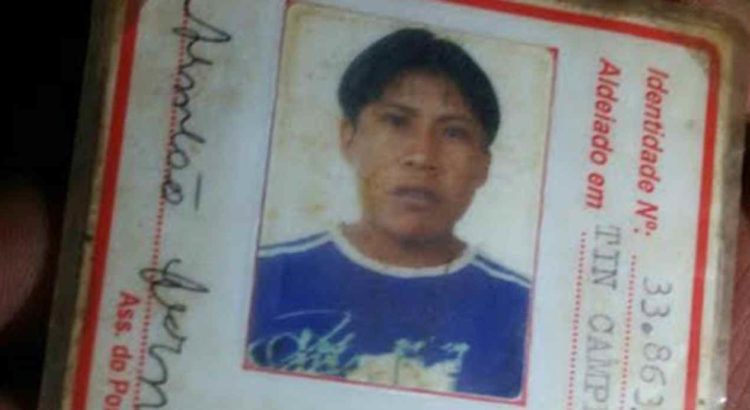

On August 30, 2015, Semião Fernandes Vilhalva, an indigenous leader of the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe, was killed in the town of Antonio João, which is 402 miles from Campo Grande, the capital of Brazil’s state of Mato Grosso do Sul (MS). The state is in the west of Brazil, on the border of Paraguay and Bolivia.

The murdered indigenous leader, Semião Fernandes Vilhalva, at the time was involved in mobilizing a lands reoccupation. He “actively participated in efforts undertaken for the recognition of indigenous territories and the recognition of the lands of the Guarani-Kaiowá people,” according to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders.

Vilhalva’s murder is part of a chain of such murders of indigenous leaders. Pierce Nahigyan of Planet Keepers describes Ambrósio Vilhalva and Marinalva Manoel, both Guarani-Kaiowá leaders:

And the list of murdered Guarani leaders goes on. Hermano de Melo, in a Sept. 13, 2015 article on the Brazilian site Environmental Racism, continues the lamentable list. De Melo alleges that there is a pattern of murders associated with reoccupation of lands. In a reoccupation of the Terra Indígena Buriti (Buriti Indigenous Territory), Oziel Gabriel, 35, murdered in Sidrolândia (Mato Grosso do Sul) in May 2013. The Guarani-Kaiowá Chief, Nísio Gomes, was murdered in the Guaiviry encampment, in Aral Moreira, MS, on the border that Brazil shares with Paraguay on Nov. 18, 2011.

It would be difficult to avoid the conclusion that the local ranchers regard it as a legitimate strategy to systematically murder the Guarani-Kaiowá leaders as a way of stamping out land disputes over ratified lands.

In 2005, the Brazilian government indeed ratified 10,000 hectares as the possession of the Guarani-Kaiowá. Yet local ranchers petitioned to have this decision overturned. As a result, the 2005 possession was never transferred. Instead, 9,317 of these hectares were divided into nine ranches, which were given into the possession of local ranchers, who now own the land, and are reluctant to give it up. The ranchers hear “reoccupation” but call it the “invasion” of indigenous people.

The remaining 150 hectares, which amounts to just .58 of a square mile, are all that the Guarani-Kaiowá have had to live on. They live in such a state of overcrowding that malnutrition, illness, and suicide have abounded. As a result, some members have squeezed onto the edge of local highways to live—as you can imagine, a precarious and dangerous situation. According to the NGO CIMI, cited in an article by Planet Keepers, 72 Guarani-Kaiowá committed suicide in 2013, “equivalent to 232 deaths per 100,000, a rate ‘that has nearly tripled over the last two decades,’ says Survival International.”

And thus, on August 30, 2015, after decades of inaction by the Brazilian government to enforce the 2005 legal demarcation of the Guarani-Kaiowá territory, Semião Vilhalva and other people of the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe were engaged in a reoccupation of the lands that had been legally deeded to them in 2005. In the town of Antonio João, people of the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe mobilized to reoccupy the lands that the Brazilian government had ratified for them—-those 10,000 hectares.

In response to the indigenous reoccupation of 4 ranches deeded to them in 2005, on Aug. 30, 2015, "about 100 people in trucks approached the Barra and Fronteira ranches, in the town of Antônio João, in order to retake the area which they view as having been invaded by the indigenous peoples," according to the newspaper Correio do Estado, which is based in and covers news based in Mato Grosso do Sul.

As the ranchers and the indigenous gathered on the disputed lands were facing off, Vilhalva, 24 years old, was searching for his 4 year old son in the crowd. He was standing on one side of a stream when, from the other side of the stream, according to the indigenous account, a gunman hired by the ranchers fired a 22 caliber revolver. The bullet hit Vilhalva's face, then exited his neck. Vilhava never found his son. As for the ranchers' account, the ranchers claim, improbably, that Vilhalva had died earlier that week and his body had only been transported to the area, and they claim it had already begun to show rigor mortis. However, the police report negated this fabrication, finding no rigor mortis on the date of the confrontation, and citing the date of death as Aug. 30. On Sept. 2, Semião was buried, attended by mourners, including his wife.

Not one person from the town who wasn’t indigenous attended the funeral, an indication of how far the two communities are from understanding one another. The climate between them is hostile, and it looks like the Federal Police are biased; Midiamax, a local newspaper, reported that the Federal Police were giving an escort for ranchers to deliver food, while the indigenous in the face-off went without escort and thus were going hungry.

Though the Federal Police have come to the area, the attacks against the indigenous have continued. According to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, more attacks have occurred:

In the photo above, leaders from 6 indigenous peoples gathered in protest of the murder of Vilhalva (Guarani-kaiowá, Terena, Munduruku, Baré, kambeba e Baniwa). Their sign reads: "We are not invaders. We're taking back what is ours!"

The Guarani-Kaiowá need long term legal protection. The Brazilian Government needs to protect their territory—those 10,000 hectares that need to be legally demarcated, again as in 2005. At this writing, the Guarani are in an unsustainable situation, and lies are being circulated by and in the media to justify the attack against Vilhalva and the Guarani.

The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders urges the following actions to pressure Brazilian authorities to act to protect the Guarani-Kaiowá in this increasingly hostile situation:

Actions requested:

Please write to the authorities in Brazil, urging them to:

Addresses:

Please also write to the embassy of Brazil. Click here to find the email of the Brazil embassy closest to you

Watch BBC Video on the Murder of Semião Fernandes Vilhalva

The murdered indigenous leader, Semião Fernandes Vilhalva, at the time was involved in mobilizing a lands reoccupation. He “actively participated in efforts undertaken for the recognition of indigenous territories and the recognition of the lands of the Guarani-Kaiowá people,” according to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders.

Vilhalva’s murder is part of a chain of such murders of indigenous leaders. Pierce Nahigyan of Planet Keepers describes Ambrósio Vilhalva and Marinalva Manoel, both Guarani-Kaiowá leaders:

Ambrósio Vilhalva was a Guarani leader who spent decades campaigning against the planting of sugar cane on his tribe’s former lands. Vilhalva starred in the award-winning film Birdwatchers and traveled the world to speak about the Brazilian government’s failure to protect native Guarani land. In December 2013, after months of death threats, Vilhalva was found dead in his hut from multiple stab wounds. See video on Ambrósio Vilhalva, murdered Guarani leader

Marinalva Manoel was also a leading figure in the Guarani Indian repatriation movement. In November 2014, she was found dead on the side of a highway after being raped and stabbed to death. Read article on Guarani murdered leader Marinalva Manoel

And the list of murdered Guarani leaders goes on. Hermano de Melo, in a Sept. 13, 2015 article on the Brazilian site Environmental Racism, continues the lamentable list. De Melo alleges that there is a pattern of murders associated with reoccupation of lands. In a reoccupation of the Terra Indígena Buriti (Buriti Indigenous Territory), Oziel Gabriel, 35, murdered in Sidrolândia (Mato Grosso do Sul) in May 2013. The Guarani-Kaiowá Chief, Nísio Gomes, was murdered in the Guaiviry encampment, in Aral Moreira, MS, on the border that Brazil shares with Paraguay on Nov. 18, 2011.

It would be difficult to avoid the conclusion that the local ranchers regard it as a legitimate strategy to systematically murder the Guarani-Kaiowá leaders as a way of stamping out land disputes over ratified lands.

In 2005, the Brazilian government indeed ratified 10,000 hectares as the possession of the Guarani-Kaiowá. Yet local ranchers petitioned to have this decision overturned. As a result, the 2005 possession was never transferred. Instead, 9,317 of these hectares were divided into nine ranches, which were given into the possession of local ranchers, who now own the land, and are reluctant to give it up. The ranchers hear “reoccupation” but call it the “invasion” of indigenous people.

The remaining 150 hectares, which amounts to just .58 of a square mile, are all that the Guarani-Kaiowá have had to live on. They live in such a state of overcrowding that malnutrition, illness, and suicide have abounded. As a result, some members have squeezed onto the edge of local highways to live—as you can imagine, a precarious and dangerous situation. According to the NGO CIMI, cited in an article by Planet Keepers, 72 Guarani-Kaiowá committed suicide in 2013, “equivalent to 232 deaths per 100,000, a rate ‘that has nearly tripled over the last two decades,’ says Survival International.”

And thus, on August 30, 2015, after decades of inaction by the Brazilian government to enforce the 2005 legal demarcation of the Guarani-Kaiowá territory, Semião Vilhalva and other people of the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe were engaged in a reoccupation of the lands that had been legally deeded to them in 2005. In the town of Antonio João, people of the Guarani-Kaiowá tribe mobilized to reoccupy the lands that the Brazilian government had ratified for them—-those 10,000 hectares.

In response to the indigenous reoccupation of 4 ranches deeded to them in 2005, on Aug. 30, 2015, "about 100 people in trucks approached the Barra and Fronteira ranches, in the town of Antônio João, in order to retake the area which they view as having been invaded by the indigenous peoples," according to the newspaper Correio do Estado, which is based in and covers news based in Mato Grosso do Sul.

As the ranchers and the indigenous gathered on the disputed lands were facing off, Vilhalva, 24 years old, was searching for his 4 year old son in the crowd. He was standing on one side of a stream when, from the other side of the stream, according to the indigenous account, a gunman hired by the ranchers fired a 22 caliber revolver. The bullet hit Vilhalva's face, then exited his neck. Vilhava never found his son. As for the ranchers' account, the ranchers claim, improbably, that Vilhalva had died earlier that week and his body had only been transported to the area, and they claim it had already begun to show rigor mortis. However, the police report negated this fabrication, finding no rigor mortis on the date of the confrontation, and citing the date of death as Aug. 30. On Sept. 2, Semião was buried, attended by mourners, including his wife.

Not one person from the town who wasn’t indigenous attended the funeral, an indication of how far the two communities are from understanding one another. The climate between them is hostile, and it looks like the Federal Police are biased; Midiamax, a local newspaper, reported that the Federal Police were giving an escort for ranchers to deliver food, while the indigenous in the face-off went without escort and thus were going hungry.

Though the Federal Police have come to the area, the attacks against the indigenous have continued. According to the Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders, more attacks have occurred:

Attacks against the Guarani-Kaiowás continue even after the killing of Mr. Semião Fernandes Vilhalva. The Nanderu Marangatu territory was attacked again on August 30 by 60 gunmen, who entered the land shooting against children, elderly people, women and indigenous men. On September 3, 4 and 5, another Guarani-Kaiowá territory was targeted by the farmers, Guyra Kamby’I, which was attacked with fire conflagration and gun shooting.

In the photo above, leaders from 6 indigenous peoples gathered in protest of the murder of Vilhalva (Guarani-kaiowá, Terena, Munduruku, Baré, kambeba e Baniwa). Their sign reads: "We are not invaders. We're taking back what is ours!"

The Guarani-Kaiowá need long term legal protection. The Brazilian Government needs to protect their territory—those 10,000 hectares that need to be legally demarcated, again as in 2005. At this writing, the Guarani are in an unsustainable situation, and lies are being circulated by and in the media to justify the attack against Vilhalva and the Guarani.

The Observatory for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders urges the following actions to pressure Brazilian authorities to act to protect the Guarani-Kaiowá in this increasingly hostile situation:

Actions requested:

Please write to the authorities in Brazil, urging them to:

i. Carry out an immediate, thorough, impartial and transparent investigation into the above-mentioned events in order to identify all those responsible, bring them before an independent tribunal, and sanction them as provided by the law;

ii. Move forward in the processes of Guarani-Kaiowá land demarcation, as delays in the finalization of such processes results in legal uncertainty and insecurity regarding land ownership and foster increased violence in land dispute;

iii. Guarantee in all circumstances the physical and psychological integrity of all human rights defenders in Brazil, including in particular land rights defenders;

iv. Conform to the provisions of the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on December 9, 1998

Addresses:

• H.E. Ms. Dilma Rousseff, President of the Federative Republic of Brazil, Palácio do Planalto, Praça dos Três Poderes, 70150-900, Brasilia DF, Brazil.

• Mr. Gilberto José Spier Vargas, Secretary for Human Rights, Secretariat for Human Rights of the Presidency of the Republic, Setor Comercial Sul - B, Quadra 9, Lote C, Edificio Parque Cidade Corporate, Torre A, 10º andar, Brasília, Distrito Federal, Brasil - CEP: 70308-200. Email: direitoshumanos@sdh.gov.br; snpddh@sdh.gov.br. Twitter: @DHumanosBrasil

• Ms. Izabella Mônica Vieira Teixeira, State Minister of the Environment, Ministry of the Environment, Esplanada dos Ministérios - Bloco B, CEP 70068-900 - Brasília/DF, Brazil. FAX: 2028-1756. Email: gm@mma.gov.br Twitter: @mmeioambiente

• Mr. João Pedro Gonçalves da Costa, President of the Indian National Foundation (FUNAI), SBS, Quadra 02, Lote 14, Ed. Cleto Meireles, CEP 70.070-120 – Brasília/DF, Brazil, Email: presidencia@funai.gov.br.

• H.E. Ms. Regina Maria Cordeiro Dunlop, Ambassador, Permanent Mission of Brazil to the United Nations in Geneva, Chemin Louis-Dunant 15 (6th Floor), 1202 Geneva, Switzerland. Fax: +41 22 910 07 51, Email: delbrasgen@itamaraty.gov.br

• H.E. Mr. André Mattoso Maia Amado, Ambassador, Embassy of Brazil in Brussels, Avenue Louise, 350 B-1050, 1050 Brussels, Belgium. Fax: +32 2 640 81 34, Email: brasbruxelas@beon.be

Please also write to the embassy of Brazil. Click here to find the email of the Brazil embassy closest to you

Watch BBC Video on the Murder of Semião Fernandes Vilhalva

Saturday, August 15, 2015

Brazilian Translations from Hilary Kaplan

Great translations of Brazilian poet Angélica Freitas, translated by Hilary Kaplan in the latest Granta magazine.

And a beautiful story from Gonçalo M. Tavares on life in Rio de Janeiro in Granta:

Read Tavares' story in Portuguese

And here are the two poems by Angélica Freitas, translated by Hilary Kaplan:

from "Artichoke":

Who can resist a poem with a bearded lady? Put that in your artichoke and smoke it.

Read "Artichoke" here

from "woman is a construct":

Read "woman is a construct" here from Angélica Freitas, translated by Hilary Kaplan

And a beautiful story from Gonçalo M. Tavares on life in Rio de Janeiro in Granta:

And that’s all there is to it: in Rio de Janeiro the average distance between humans is shorter. And that carries enormous consequences.Read Tavares' story here

When I walk through Rio de Janeiro, I see moving human spots. It’s the only city, even in Brazil, where skin colour truly doesn’t exist. In other cities, when a white man and a black man walk side by side, even in strong and most excellent companionship, I see the black and I see the white. Not in Rio. In Rio, there are spots of people. After a spot of two, a blot of four, another of six, only with great effort will I be able to make out the colours (like an amateur art critic). Out of those spots come – and we realize this only with great effort, almost artificially – a black man, a mixed race man and a white man (for example).

The average distance between two people, then: the smallest in the world.

Read Tavares' story in Portuguese

And here are the two poems by Angélica Freitas, translated by Hilary Kaplan:

from "Artichoke":

the bearded lady simply didn’t feel

the need to discuss

every little everyday thing

Who can resist a poem with a bearded lady? Put that in your artichoke and smoke it.

Read "Artichoke" here

from "woman is a construct":

woman is basically meantGeesh, I hope not!

to be a residential complex

all the same

all plastered over

just in different colors

Read "woman is a construct" here from Angélica Freitas, translated by Hilary Kaplan

Saturday, August 8, 2015

I Want the Plasma

Because no one can hold me back now. I can still reason—I studied mathematics, which is the madness of reason—but now I want the plasma—I want to eat straight from the placenta.—Clarice Lispector from Agua Viva

Friday, July 4, 2014

F--- - The Cup?

Mixed feelings about the World Cup. Totally excited to see Brazil and Colombia play. However, I’m dismayed at the manner in which protests at the start of the cup were brutally put down--to the point that we don’t see such protests now. Military force effectively created a climate of fear, which suppressed protest.

This might not be so worrisome if we hadn’t noticed other recent antidemocratic moves: for example, when the Supreme Federal Tribunal ignored constitutionally required processes of consulting indigenous people before approving enormous hydroelectric projects, including Belo Monte Dam.

According to the People’s Portal of the Cup, “the level of political repression of protestors during the 2014 World Cup, put on by FIFA, has proved to be beyond the level acceptable in a democratic state.” (July 1, 2014) Read more in Portuguese.

Here's a poem by my friend, Alex Simoes, poet & activist. Even before the cup, he and other citizens of Salvador, Bahia, were struck by tear gas as they tried to protest.

This World Cup in 2014 in Brazil has cost more than the last 4 World Cups--why?

This might not be so worrisome if we hadn’t noticed other recent antidemocratic moves: for example, when the Supreme Federal Tribunal ignored constitutionally required processes of consulting indigenous people before approving enormous hydroelectric projects, including Belo Monte Dam.

According to the People’s Portal of the Cup, “the level of political repression of protestors during the 2014 World Cup, put on by FIFA, has proved to be beyond the level acceptable in a democratic state.” (July 1, 2014) Read more in Portuguese.

Here's a poem by my friend, Alex Simoes, poet & activist. Even before the cup, he and other citizens of Salvador, Bahia, were struck by tear gas as they tried to protest.

hell, I’ll tell ya, fuck the cup! “damn,

you’re messed up.” I’ll tell all, notwithstanding

I have so many reasons for screaming thus,

that it makes me happy to not have near at hand

such a grenade. skin open

& tears spouting are not the whole of the complaint.

it’s that I’m run rough trying to express

myself where, on the contrary,

protest is not possible. only because “in the end

it’s one immense political boondoggle”: coverup.

hell, I’ll tell ya, “there’s no need

for the use of bombs for moral effect

nor deployment of tear gas as a creed.”

yup, I say: fuck the world cup.

This World Cup in 2014 in Brazil has cost more than the last 4 World Cups--why?

ora (direis), foda-se a copa! “certo,

perdeste o senso”. e eu vos direi, no entanto

que para assim gritar eu tenho tantos

motivos, que me alegra não ter perto

de mim uma granada. o peito aberto

e a lágrima escorrendo não é quebranto,

é que tenho passado pelo aperto

de me manifestar onde, no entanto,

não é possível. só porque, “no fundo,

tudo é uma imensa ignorância política”,

ora direis, “que não é nada crítica

a utilização de bombas de efeito

moral e o gás lacrimogênio é bem feito”.

eu digo: foda-se a copa do mundo.

Saturday, June 14, 2014

Before World Cup, Forced Removals of Salvador, Bahia Residents

You’ve probably heard about street protests in Brazil around the World Cup. But what exactly are the protesters’ complaints? One critique that hasn't reached the global media, but has been much discussed via word of mouth, is the following. In pre-World Cup preparations, Salvador's government conducted illegal removals of residents, sometimes to sanitize an area of poor residents. I had occasion to have a little glimpse of the “after” effect of such removals, and I'll share what I've heard from friends in the World Cup host city of Salvador.

In Jan. 2014 in Salvador, Bahia, I observed firsthand evidence that the government had cleared the area of poor residents. My hosts, Dalila Pinheiro and her partner, Sereno, were driving us along the low road that hugs the border of the Bay of All Saints. Salvador is divided into what locals call the high city and the low city, Cidade Alta and Cidade Baixa. There is actually a geographical fault that divides the two parts of the city, making the high city rise quite abruptly over the low, like a castle overlooking lowlands.

As we drove on the low road, Sereno (yes, it does mean Serene—his parents raised him in a hippie alternative community on the edge of Salvador) pointed out notable features.

Sereno gestured far up toward a structure jutting out from the steep escarpment above, and connected by a thin, high column to the lower city. This is the Elevador Lacerda, at 236 feet high the main transport between high and low city. The Elevador transports people to and from the Plaza Cairu to the Plaza Thomé da Souza, where a central market is located, and major free concerts take place. A week or so later, I would hear Brazilian pop giant Daniela Mercury play in the lower plaza.

Elevator seems a strange word for what is, since every other elevator I’ve known has been inside a building, guarded in its core. This elevator is 236 feet high, a stand-alone, straight up and down column. From its well-fortified base in the upper hillside, a long “hallway” juts straight out, in width and depth mirroring the column it adjoins, forming in shape something like half a picture frame.

Later that week after New Year's 2014, when I was up at the top of the Lacerda, waiting to go down to the Daniela Mercury concert, I stood in line with hundreds of others, the line filing through the upper hallway, surrounded on both sides by glass. The line is enough of a fixture that a small stand sells coffee, soda, and snacks for your wait. To the left was an orange smear over the Bay of All Saints. Dimly perceived was the fact of boats in the bay. The view was less than clear, as the slightly tinted glass was greased with swipes of what must have been a day of body parts nudging nearer to the would-be spectacular view.

Driving now with Dalila and Sereno below the Lacerda, I followed his finger as he pointed up the steep hill toward it. Beneath the form of the signature structure, a green lawn adjoined its base, running in length perhaps an 1/8 of a mile.

The lawn cued my U.S. self, trained to see green lawn around public edifice—say, a capitol building, a stately Frank Lloyd Wright-designed public garden—as a mark of the distinguished quality of said edifice.

“Nice!” I thought, as I craned my neck up toward the wall of the upper city edged by a swath of green unusual in Salvador.

If I’d thought a moment, I might have wondered: In a city crowded with poor, where every meter is contested and used territory, how would such an unfenced section of lawn have come about, here in the center of Salvador?

The unasked question found its answer in the next moment. Dalila explained that the government had expelled the poor families who had been living in crowded buildings, which were razed. The relatively tidy green, to which my U.S. self responded as a marker of beauty and social order, in fact indicated the opposite, an unseemly uprooting of families, many of whom had been living in the spot, growing community for generations. These families had been on this spot in the descriptions of novelist and son of the city Jorge Amado, who wrote his famous novels on the city and its denizens.

According to my friend, Salvador resident, writer and activist Alex Simões, the residents were removed in the middle of the night from their houses. He cites about 70 persons being removed from their houses in the area around the Ladeira da Preguiça, made famous by Brazilian classic singer Elis Regina. A ladeira is a very steep street, a kind of alleyway. The city government claimed, as pretext for the residents’ expulsion, that the path moving through the community had been unsafe and filled with crack users. My friend, poet Nilson Galvão, also a Salvador resident, adds that he heard that some of the people removed in the middle of the night were taken to shelters. Alex reports that some others are in very simple hotels (probably our equivalent would be SROs or boarding houses), which, for now, the city is paying for.

After this first wave, uprooting families who had lived in the area for generations, the city implemented other actions to clear the area. I was shocked to hear from Alex Simões that the city arranged for a big truck to go through the streets, literally washing, with high force water jets, the streets. Anyone living on the streets was literally washed away. As Alex ironically noted, "Solution: no beggars in the city center." And then, quickly were put on the city's books two ordinances that allow for dozens of buildings to be appropriated "for public ends." Public use for these cleared-out buildings has yet to occur, leading Alex to suspect collusion between city government and private hotel companies, which have long wanted to create a hotel zone of this area.

Dalila reports that, since I visited, even more removals have occurred around the general area of the Avenida Contorno, near to the Marina Bahia. The removals include the Ladeira of the Mountain. When I told her I couldn't find much online to do with the removals, she noted that this is not by chance, as the media channels in Salvador have observed a blackout on the theme.

These removals in Salvador are part of a larger trend of pre-World Cup actions. According to the Portal Popular da Copa in an article dated March 4, 2014, on that day in the 22nd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, Giselle Tanaka, from ANCOP (National Articulation with the Public Committees of the Cup), would present briefly on forced removals made in the context of preparation for the World Cup and for the Olympics. ANCOP would ask the Council to demand that the Brazilian government stop all forced removals of people, make a plan to give removed residents reparations, and a plan to guarantee human rights in the future in unforseen removals by act of nature. To read more in Portuguese, click here.

Later that week in Jan. 2014, after I heard Daniela Mercury play a night concert on the Plaza Thomé da Souza, packed body to body (most of them taller than mine), I was grateful to push through the crowd to stand in line to be elevatored back. Once securely back in the Plaza Cairu, I took advantage of the sudden availability of extra oxygen, not returning right away to Dalila and Sereno's apartment in Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, but tarrying a bit on the ramparts to the side of the Elevador Lacerda. With the other night lingerers, citizens of Salvador and Brazilian tourists, I leaned against the stone wall and looked out across the distance to the little lights of small boats in the Bay of All Saints.

And every so often, which is to say often, I looked down the steep incline to the lower city, where new, white lights illuminated the bright green lawn below, impeccable as a park.

Thanks to Dalila Pinheiro, Alex Simões, and Nilson Galvão for their reportage.

In Jan. 2014 in Salvador, Bahia, I observed firsthand evidence that the government had cleared the area of poor residents. My hosts, Dalila Pinheiro and her partner, Sereno, were driving us along the low road that hugs the border of the Bay of All Saints. Salvador is divided into what locals call the high city and the low city, Cidade Alta and Cidade Baixa. There is actually a geographical fault that divides the two parts of the city, making the high city rise quite abruptly over the low, like a castle overlooking lowlands.

As we drove on the low road, Sereno (yes, it does mean Serene—his parents raised him in a hippie alternative community on the edge of Salvador) pointed out notable features.

Sereno gestured far up toward a structure jutting out from the steep escarpment above, and connected by a thin, high column to the lower city. This is the Elevador Lacerda, at 236 feet high the main transport between high and low city. The Elevador transports people to and from the Plaza Cairu to the Plaza Thomé da Souza, where a central market is located, and major free concerts take place. A week or so later, I would hear Brazilian pop giant Daniela Mercury play in the lower plaza.

Elevator seems a strange word for what is, since every other elevator I’ve known has been inside a building, guarded in its core. This elevator is 236 feet high, a stand-alone, straight up and down column. From its well-fortified base in the upper hillside, a long “hallway” juts straight out, in width and depth mirroring the column it adjoins, forming in shape something like half a picture frame.

Later that week after New Year's 2014, when I was up at the top of the Lacerda, waiting to go down to the Daniela Mercury concert, I stood in line with hundreds of others, the line filing through the upper hallway, surrounded on both sides by glass. The line is enough of a fixture that a small stand sells coffee, soda, and snacks for your wait. To the left was an orange smear over the Bay of All Saints. Dimly perceived was the fact of boats in the bay. The view was less than clear, as the slightly tinted glass was greased with swipes of what must have been a day of body parts nudging nearer to the would-be spectacular view.

Driving now with Dalila and Sereno below the Lacerda, I followed his finger as he pointed up the steep hill toward it. Beneath the form of the signature structure, a green lawn adjoined its base, running in length perhaps an 1/8 of a mile.

The lawn cued my U.S. self, trained to see green lawn around public edifice—say, a capitol building, a stately Frank Lloyd Wright-designed public garden—as a mark of the distinguished quality of said edifice.

“Nice!” I thought, as I craned my neck up toward the wall of the upper city edged by a swath of green unusual in Salvador.

If I’d thought a moment, I might have wondered: In a city crowded with poor, where every meter is contested and used territory, how would such an unfenced section of lawn have come about, here in the center of Salvador?

The unasked question found its answer in the next moment. Dalila explained that the government had expelled the poor families who had been living in crowded buildings, which were razed. The relatively tidy green, to which my U.S. self responded as a marker of beauty and social order, in fact indicated the opposite, an unseemly uprooting of families, many of whom had been living in the spot, growing community for generations. These families had been on this spot in the descriptions of novelist and son of the city Jorge Amado, who wrote his famous novels on the city and its denizens.

According to my friend, Salvador resident, writer and activist Alex Simões, the residents were removed in the middle of the night from their houses. He cites about 70 persons being removed from their houses in the area around the Ladeira da Preguiça, made famous by Brazilian classic singer Elis Regina. A ladeira is a very steep street, a kind of alleyway. The city government claimed, as pretext for the residents’ expulsion, that the path moving through the community had been unsafe and filled with crack users. My friend, poet Nilson Galvão, also a Salvador resident, adds that he heard that some of the people removed in the middle of the night were taken to shelters. Alex reports that some others are in very simple hotels (probably our equivalent would be SROs or boarding houses), which, for now, the city is paying for.

After this first wave, uprooting families who had lived in the area for generations, the city implemented other actions to clear the area. I was shocked to hear from Alex Simões that the city arranged for a big truck to go through the streets, literally washing, with high force water jets, the streets. Anyone living on the streets was literally washed away. As Alex ironically noted, "Solution: no beggars in the city center." And then, quickly were put on the city's books two ordinances that allow for dozens of buildings to be appropriated "for public ends." Public use for these cleared-out buildings has yet to occur, leading Alex to suspect collusion between city government and private hotel companies, which have long wanted to create a hotel zone of this area.

Dalila reports that, since I visited, even more removals have occurred around the general area of the Avenida Contorno, near to the Marina Bahia. The removals include the Ladeira of the Mountain. When I told her I couldn't find much online to do with the removals, she noted that this is not by chance, as the media channels in Salvador have observed a blackout on the theme.

These removals in Salvador are part of a larger trend of pre-World Cup actions. According to the Portal Popular da Copa in an article dated March 4, 2014, on that day in the 22nd session of the United Nations Human Rights Council, Giselle Tanaka, from ANCOP (National Articulation with the Public Committees of the Cup), would present briefly on forced removals made in the context of preparation for the World Cup and for the Olympics. ANCOP would ask the Council to demand that the Brazilian government stop all forced removals of people, make a plan to give removed residents reparations, and a plan to guarantee human rights in the future in unforseen removals by act of nature. To read more in Portuguese, click here.

Later that week in Jan. 2014, after I heard Daniela Mercury play a night concert on the Plaza Thomé da Souza, packed body to body (most of them taller than mine), I was grateful to push through the crowd to stand in line to be elevatored back. Once securely back in the Plaza Cairu, I took advantage of the sudden availability of extra oxygen, not returning right away to Dalila and Sereno's apartment in Santo Antônio Além do Carmo, but tarrying a bit on the ramparts to the side of the Elevador Lacerda. With the other night lingerers, citizens of Salvador and Brazilian tourists, I leaned against the stone wall and looked out across the distance to the little lights of small boats in the Bay of All Saints.

And every so often, which is to say often, I looked down the steep incline to the lower city, where new, white lights illuminated the bright green lawn below, impeccable as a park.

Thanks to Dalila Pinheiro, Alex Simões, and Nilson Galvão for their reportage.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.gif)